Financial Aid Helps National Guardsman and Special Education Teacher

At the start of the year, one semester separated Renee Villareal from earning a degree in Special Education. One semester stood between her and starting a career teaching kids and adolescents diagnosed with physical and mental learning needs.

Her years-long endeavor started in high school, fueled by what she saw as malicious attacks on the boys and girls whose impediments made them targets of harassment. They were teased and bullied because of how different they looked and spoke. Some were called "stupid,” while others were called “lazy.”

Villarreal was not one to stand idle and watch. She felt the instinct to charge to their defense. It was the right thing to do, no doubt, and it came as second nature.

Both her parents served in the military, which is how Villarreal inherited their values and sense of duty. Standing up for the rights of others, and advocating for kids with disabilities became her mission ever since her time as a student at Lyman Hall High School.

"I realized this is what I’m going to be good at. I want to be a teacher,” she said. "I want to help and stick up for these kids that need me.”

At Southern Connecticut State University, where Villarreal is currently an undergraduate, her fieldwork in Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy puts her side-by-side teaching children with autism.

Under the guidance of an accredited therapist, she develops individualized lesson plans focused on improving her client’s interpersonal behavior and learning skills.

At the same time, for the last two years, Villarreal has been serving part-time in the Connecticut Army National Guard, attached to the aviation unit of the 1109th Theater Aviation Sustainment Maintenance Group.

Joining the National Guard was her way of fulfilling her patriotic duty and honoring her parents’ service. The pay isn’t much, she admits, so to make ends meet, she supplements her income from the army and therapy by working a few days a week at the neighborhood PetSmart.

Up until the second week of March, she was living paycheck-to-paycheck. But the 23-year-old single mother, the sole breadwinner with a two-and-a-half-year-old daughter, was unprepared for the public health pandemic sweeping across the country.

A crisis loomed on the horizon.

On March 8, Governor Ned Lamont announced the state’s first confirmed case of COVID-19. The dominos fell right after with COVID-19 infections popping up in counties throughout the state.

Southern Connecticut State University closed its campus, opting to deliver the curriculum online for the next semester, which pushed Villarreal’s fieldwork courses from the spring term to the fall. It also pushed back her graduation date to later in the year.

One by one, her primary sources of income started drying up. The National Guard reduced her service hours, and with that, a drop in her monthly paycheck. Parents of her clients canceled ABA therapy sessions for the foreseeable future. And a number of part-time employees at PetSmart, including Villarreal, were furloughed.

Her life was upended in a matter of weeks. “How am I going to pay rent?” she asked herself. “How am I going to put food on the table?”

Sleepless nights beget sleepness nights. Alone and caring for her daughter with limited resources at her disposal, Villarreal was overcome by a cruel mixture of stress and depression.

Standing amongst the throngs of people waiting in line at the local food bank one day, Villarreal felt she had hit rock bottom.

"I felt like a bad mom because I wasn’t able to provide,” she said. "No mom wants to feel that way.” As her finances started dwindling, Villarreal had her reasons for hesitating in asking for help.

"In my mind, I’ve always done everything by myself,” she said while ticking off a list of life decisions she made independently of others from enlisting in the army and working multiple jobs to paying for her bills and education.

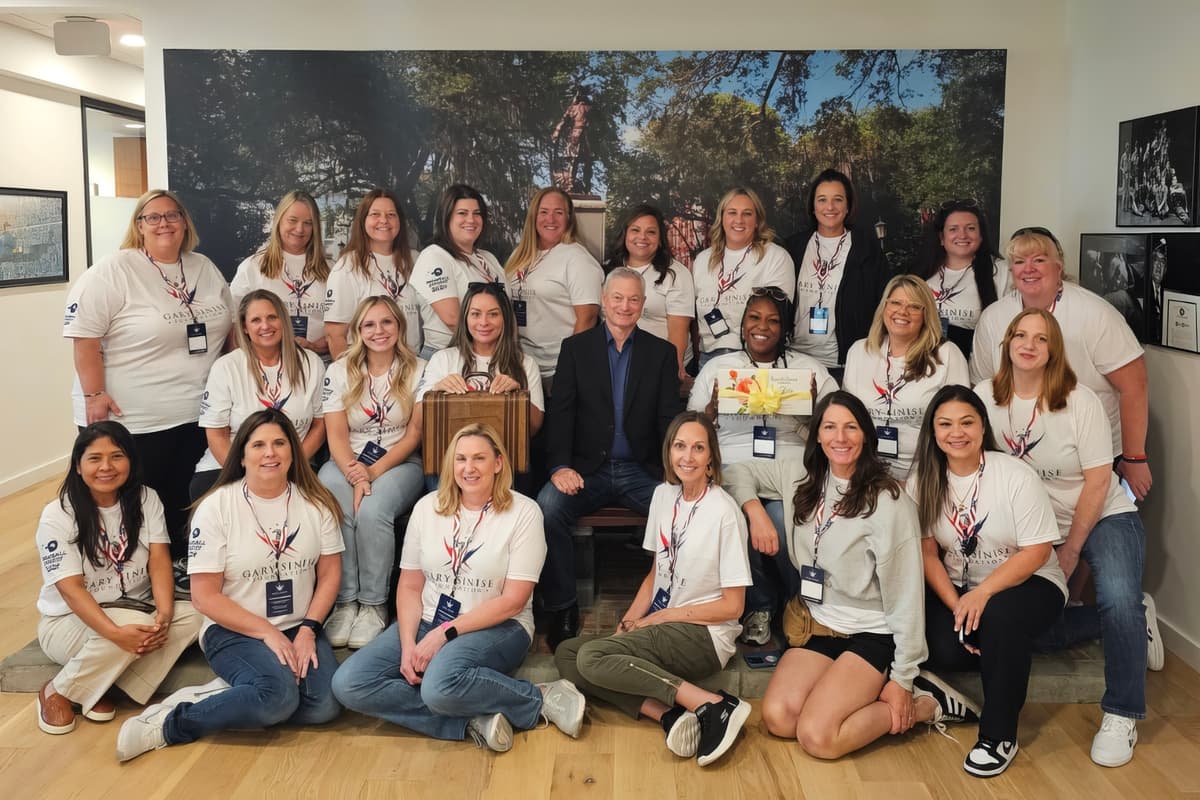

By the time she contacted the Gary Sinise Foundation at the end of March seeking financial assistance, Villarreal said her situation was making her “drown with worry.”

"I put in all my effort to try to make the best life for my daughter and me that I can. I felt like it was all about to go down.”

To keep her afloat, the Foundation paid two months of her rent through the Emergency COVID-19 Combat Service fund. Villarreal also received a Walmart gift card to cover the costs of groceries and other out of pocket expenses, such as buying diapers.

"The foundation literally changed my life,” she said. "I don’t know how I would have made it without them.” In a matter of days after receiving help from the Foundation, Villarreal has experienced an about-face in her life.

No more waiting in line at the food bank with her fingers crossed that staples such as milk and eggs will be available, and more importantly, not past their expiration date. No more stressful days and sleepless nights that mired her for weeks on end.

"It’s scary to think that I could have lost everything I’ve worked so hard for,” she said about being embarrassed and afraid to ask for help. In short order, she and her daughter, Natalie, have become glued at the hip.

"I’m able to really take advantage of my time now and just catch up with myself,” she said about having time to relax and read a book or take Natalie outdoors to go fishing and to the park.

When Villarreal graduates this fall, she will be among a growing number of professionals nationwide who are entering an in-demand occupation.

Projections from the Connecticut Department of Labor show a dearth of special education teachers at the primary and secondary school levels. Increasing numbers of children over the years have been diagnosed with a physical or mental disability that adversely affects their ability to learn in the classroom, explained Villarreal.

In the 2015-16 school year, more than 70,000 students in kindergarten to 12th grade in the state of Connecticut required special education. That number has since ballooned in the last five years to well over 79,000 students representing 15.6% of the state’s student population.

Despite the uncertainty of what lies ahead for her and Natalie with the state yet to see a bend in its curve of coronavirus cases, Villarreal remains focused on becoming a special education teacher.

"If you want to do something great in life,” she said, “you have to be willing to put in the work, the time, and eventually everything else just comes easily.”

And in her case, a little bit of help goes a long way.