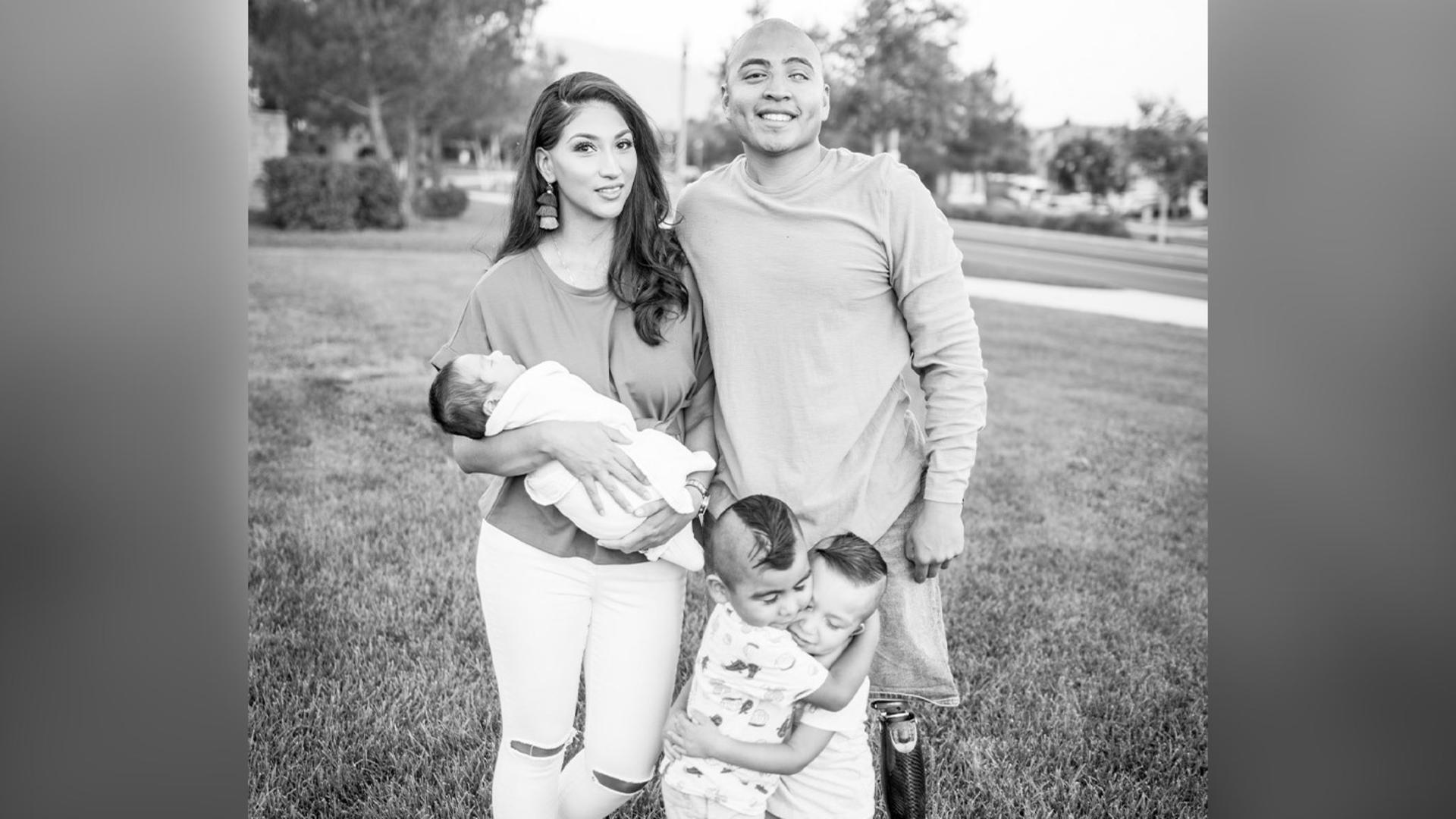

Southern California Marine and family ready for new life in specially adapted smart home

February 8th, 2021

Next month, Josue Barron and his family will move into a specially adapted smart home not far from their residence in Temecula, Calif. The mortgage-free home provided by the Gary Sinise Foundation’s Restoring Independence Supporting Empowerment (R.I.S.E.) program has been over two years in the making.

The move comes as a welcome relief for the retired Marine and father of three boys. In a way, it culminates the direction he’s taken his life since an improvised explosive device (IED) derailed it nearly eleven years ago. And it will finally put an end to too many frustrations performing what anyone who is able-bodied can describe as effortless — the household chores and movements between rooms that are never given a second thought.

Like a chronicle of his life, the tattoos inked on his body tell an intriguing story.

One tattoo reminds him of an unprivileged upbringing. There’s the shield of his infantry, the “Darkhorse” battalion, from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment. Another depicts the 2010 injury in Afghanistan. Across his chest, up and down his left arm, and scrawled along his back, some tattoos remind him of who he is and where he came from. Others remind him of what he has sought and what he has gained in life: purpose.

The streets were supposed to fill the void left by his estranged father. He was an impressionable teenager looking for male role models. Instead, Barron saw gang life in southeast Los Angeles and the crew he ran with for what they were: A false sense of identity. A false sense of purpose.

“No matter where I would go, the way I dress, the way I look, the mentality that I had, I was always going to attract other gang members to come up to me and ask me where I’m from,” Barron said of growing up in Cudahy. Beyond the borders of the 1.23-mile predominantly Latino city, he said, “No matter where I went, I was already a threat. And my mindset was that everybody was a threat to me.”

Factory work wasn’t the future he saw for himself after high school, unlike his single mother, who didn’t have a choice what with seven mouths to feed, including hers. Rival gang members at the nearest community college made it too dangerous for him to pursue higher education.

The Marine Corps changed his life.

“I never had confidence in myself growing up. I didn’t believe in myself,” Barron explained. He enlisted in 2007 as a 17-year-old who graduated from Boot Camp more self-assured — no longer a follower but a leader.

He found purpose. He found self-confidence. And he found a future. Three years later, the purpose he found in the Marine Corps and the future he was counting on in the military went up in smoke.

In October 2010, the Darkhorse battalion was sent to Camp Leatherneck, Afghanistan, to replace Marines from 1st Division, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines (3/7). It was Barron’s first deployment to a warzone.

“These guy’s faces looked like zombies,” he recalls of seeing Marines from the 3/7 at Camp Leatherneck. Their fatigues were covered in dirt, boots blackened by combat. “When I first saw them, I knew that these guys were different, and I saw what we were going to go through in these guys.” Their disposition said it all.

“They look like they just woke up from a nightmare.”

Marines from Darkhorse took up a position in Sangin in Afghanistan’s Helmand province. Casualties were on the rise.

Until Barron’s unit began making its way back to their outpost on the morning of October 21, the IED that had been planted overnight by the Taliban, remained undetected. “I always thought that I was going to die or that I was going to get shot. But I never thought about losing a limb,” Barron said of his mindset.

The IED was triggered along the patrol route. Barron lost his left leg and left eye; the unit’s engineer lost both his legs and several fingers. They were not the last to be maimed or killed during the battalion’s seven-month deployment.

The Darkhorse battalion returned to Camp Pendleton in April 2011 with the highest casualty rate of any Marine unit since the war in Afghanistan began. The figures are grim: 25 dead, 184 wounded. And like Barron and his engineer, 34 lost at least one limb.

In 2013, after he recovered at Naval Medical Center in San Diego, Barron, his wife, Debbie, and their sons moved an hour north into a two-story home in Temecula. Frustration and anger followed Barron in the non-adaptive house. There were no grab bars, handrails, or a bench built into the shower. No pull-down cabinets in the kitchen. And no wheelchair access to the garage. He applied to the Gary Sinise Foundation R.I.S.E. program in 2017.

The onus of the homebuilding process for a specially adapted smart home is a collaborative effort. In July 2019, the Barron’s began working with the Gary Sinise Foundation’s R.I.S.E. team. Months of discussions were held before the ground was broken a year later, explained Pete Franzen, a R.I.S.E. project manager.

There are no trivial questions in designing a home to fit a disabled veteran’s needs, “Force them to talk about things that honestly they don’t really want to talk about,” Franzen said. No detail is too small or too private.

“When you go to use the toilet,” Franzen asks, “do you want to come at it from the left side or the right side?” Whatever the answer, the home is carefully designed to ensure comfort and independence, in the bathroom and elsewhere, just as important as having three-foot-wide doorways, grab bars installed in the shower, and a wheelchair-accessible kitchen. “They build around my disability,” Barron said.

Debbie, for her part, is eager to see her husband no longer frustrated at home. Instead of him dwelling on the little things that irk him, she said she’s excited to see the independence he’ll soon have, including spending more time with the kids. “I’m excited for, just, everything. It’s, like, unreal. It’s real. It’s a blessing.”

The Barron’s are preparing in earnest for the move next month; the home dedication is on March 4. They won’t be going far. Temecula remains their home and future.

At the same time as they are packing up boxes and donating unwanted furniture, clothes, and other items to Goodwill, Barron is preparing for the Paralympic handcycling trials this summer and the 2022 Invictus Games. His track record already boasts medals won in several adaptive sports competitions including the Warrior Games and the 2018 Invictus Games in Sydney, Australia.

Since last March, he has been cycling 100 miles a week, splitting workouts between interval training, time trials, and building endurance. “Everything that I do now has to have a purpose,” Barron said. Making Team USA’s roster and counting himself among the world’s elite athletes competing in either the 2024 or 2028 Olympics is that purpose.

But that “purpose” encapsulates so much more than athletic feats — and he knows it.

“Everything I’ve been through, I feel that I have to never forget where I come from,” Barron said. “I know that there are people that are going to go through the same thing that I went through. Maybe kids in L.A. don’t have to join the military to change their lives forever, but they can see that there’s a different world out there, and I can show them that.”