World War II veteran opens up about air war in Europe, and gratitude for the Gary Sinise Foundation

May 17th, 2021

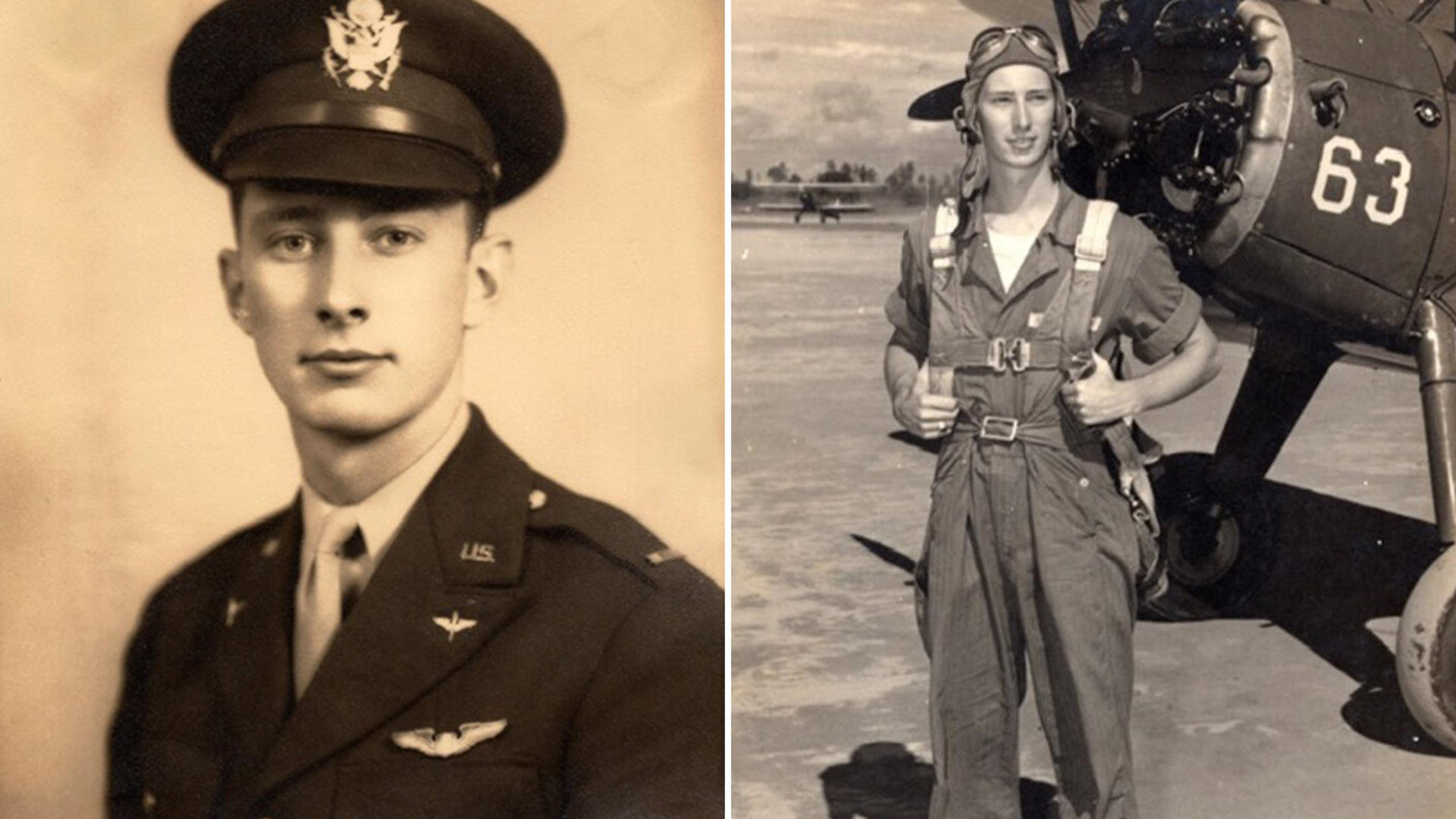

John Luckadoo was only weeks removed from the air war in Europe when he joined his parents one Sunday morning at their local Baptist church in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He had flown his last combat mission, 25 in all, as a B-17 pilot on February 13, 1944. He was 22 yet older beyond his years.

Sitting next to his parents, the pastor called on him. “John, tell us what it was like.” Luckadoo rose from the pew, rather surprised by the pointed question and unwanted attention.

“Pastor, with all due respect,” he said, “I think the reason we served was to keep you from having to know what it was like.”

Since that day in mass, and for much of his adult life, he kept silent about his service during the war.

“It was a period in my life that was compartmentalized. It was a chapter where I experienced terrible things, saw terrible things happen — was grateful to have survived it,” Luckadoo, now 99, said. “But it was nightmarish to try and recall it.”

For 50 years, he said he never shared his memories while flying with the 100th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force. Not with family or anyone else. The group known as “The Bloody Hundredth” suffered staggering high casualties: one in four crew members survived the war.

“I wanted to forget it. I really wanted to forget it.”

Luckadoo goes by Lucky, a nickname he earned while flying bombing runs over Nazi-occupied France and Germany. In recent decades he has opened up about what he witnessed in the air.

In 2017, Lucky and a group of World War II veterans and high school students from Dallas visited the National WWII Museum in New Orleans. The Gary Sinise Foundation organized the three-day trip known as Soaring Valor. Said Luckadoo, “We got to relay to the youngsters who really never had the opportunity to hear it from the horse's mouth as to what it was like to defend the freedom that we enjoy today.”

“You always wonder exactly why you were spared, but I do feel that it is my obligation to try to relate to successive generations, as best I can, something of what it was like to be called upon to serve your country and to put your life on the line in order to sustain and preserve our freedoms because they’re so precious to us.”

In September 2020, the foundation, in coordination with the National WWII Museum, began mailing care packages to World War II veterans. Among the dozen or so items included in each box are a copy of Sinise’s autobiography, “Grateful American,” and World War II-themed postcards. Nationwide, 276 packages have been delivered.

“I was very pleased to have Gary [Sinise] think so highly of us that he would send us that care package. It was quite a pleasant surprise,” said Luckadoo, whose package arrived last September. “I’m particularly grateful that he shared his book...what he has done for veterans, in particular, and his passion for recognizing our sacrifices and service is just most gratifying.”

By the war's end in 1945, 36 of Luckadoo’s 40 classmates from flight school had either withdrawn from flying, been shot down, or killed in action.

Before leaving the States for England, he remembers the blunt assessment he and other aircrews received from their commander: “We were going to be killed, and you might as well accept it.” Instead of focusing on the odds of survival, commanders suggested aircrews focus on what the job was “to bring Germany to its knees.”

Achieving that job and surviving a tour of 25 missions, Luckadoo said, “It didn’t really matter how well you performed, or what you did or what you didn’t do, it was a matter of pure luck if you came through.”

Taking off from their air base at Thorpe Abbotts, England, the air war in 1943, Luckadoo explained, was an “uneven playing field.” Compared to the inexperienced citizen-soldiers from the States, Luftwaffe pilots were experienced and combat-tested. But while flying at 25,000 feet, American pilots grappled with another enemy.

“We were in unpressurized airplanes five miles above the ground, and we were enduring temperatures in the minus fifty to sixty degrees below zero area,” Luckadoo said about conditions inside the Boeing-built B-17. Despite the frigid environment, the mental and physical energy spent flying in formation while concentrating on the mission, Luckadoo exclaimed, “We suddenly found ourselves sweating like a whore in church.”

Perspiration was so profuse, he remembers, that ice blocked the air flow into his oxygen mask. “We had to take one hand and break off the ice crystals and fly the airplane with the other.”

On many bombing runs targeting German ball-bearing factories, synthetic oil manufacturing plants, and submarine pens, he watched in agony as aircraft from his squadron and formation were shot down or blown out of the sky.

“The trauma, the horror, the chaos, the impact on your psyche could be so pronounced that you’d turn white-headed in the course of one mission.”

After each mission, “You thank your lucky stars that you’re alive, but you don’t have much opportunity to dwell on it,” Luckadoo said about aircrew casualties. “You can’t afford to. You think that the guy on each side of you — to your right and to your left got shot down and you didn’t — because you knew you would have to go back out and do it again the next day.”

Over Memorial Day weekend, Luckadoo will join a thinning population of World War II veterans participating in a flag ceremony at the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force. Twenty-six thousand 48-star flags will be planted in the memorial garden in Savannah, Georgia, commemorating 26,000 crew members from the Mighty Eighth killed in the war.

“We seldom see the casualties,” Luckadoo said about the difference between fighting in the air and on land. “If they go down in flames, or if they’re shot down from the air, there’s no burial, there’s no funeral, there’s no ceremony that commemorates that loss of that airman.”

One airman, in particular, will be at the forefront of his thoughts that day.

“A very popular guy, he was president of our class in high school and commanded the ROTC regiment,” Luckadoo said of his best friend, Leeroy “Sully” Sullivan.

Sullivan joined the Royal Canadian Air Force months before the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor. He flew with the RAF in Egypt and North Africa in 1942. A year later, as his aircraft took off from a base in England, its engine failed and plunged to the ground. He was killed instantly.

Sullivan’s death, Luckadoo said, “was more significant, and more memorable to me, than any other losses that I experienced among comrades that I was flying with in the group.”

“We were like brothers.”

Far from Sullivan’s grave at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey, England, Luckadoo, the last surviving B-17 pilot from the 100th Bomb Group, will plant a flag in his memory.